Over the last few days, I’ve had a number of conversations with both right- and left-leaning friends about the political futures of Al Franken and Roy Moore. Without equating the severity of the alleged offenses (Moore’s are obviously worse), I’ve been struck by the extent to which people across the political spectrum will tolerate misconduct in politicians that they’d never, ever tolerate in their own workplaces.

In most functioning corporations, if there’s pictorial evidence that a senior executive groped a woman, then that executive is forced to resign. If there are known, credible allegations that an applicant for a senior position has sexually assaulted teenage girls, then no sane employer gives him a job.

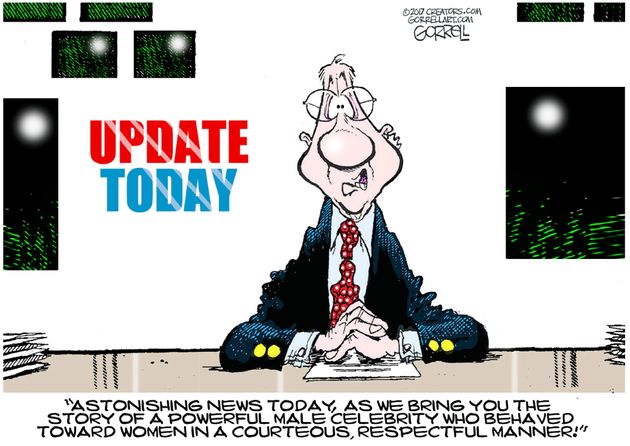

In fact, in the post-Weinstein era it’s remarkable to see how quickly corporate Hollywood and corporate media can move, even against some of the biggest names in news and show business. Credible claims have led to swift action. Men have been fired. Entire magazines have been canceled. Television shows have been shut down. All of this is evidence that maybe, just maybe, we’re on the cusp of a culture change.

So why do politicians continue to avoid responsibility for the same actions that cost private citizens their jobs? Two of the last four presidents have been credibly accused of sexual misconduct, including sexual assault. We learned last week of congressional sexual-harassment settlements that are still mysterious to the public. And now we face the very real possibility that the world’s greatest deliberative body will feature a man who once abused teenage girls and who will be seated near a man who was caught on camera groping a sleeping model.

Why do politicians escape when private citizens face consequences? There are two main answers: an inflated sense of importance and the reality of the binary choice. Politicians and their allies have become very good at communicating their own importance. A senator isn’t just a senator, he’s a “champion” of women’s rights or a “warrior” for the Constitution. Consequently, they convince the public (and themselves) that if they lose their jobs, a great cause will suffer. This argument becomes ever more potent as our body politic relentlessly (and wrongly) elevates politics over culture. Indeed, it sometimes holds even when a political party wouldn’t suffer a net loss by exercising the same level of discipline that’s expected in virtually every other quarter of American life. If Bill Clinton had resigned in 1998, he would have been replaced by Al Gore, and the 2000 election (not to mention everything that followed) might have turned out differently. If Al Franken were forced to resign today, he would be replaced by another progressive Democrat.

Are these men really so gifted and important that their survival should trump not just the ascension of their progressive peers but also their negative impact on our culture? Is Franken such a powerful champion of progressive causes that, say, Keith Ellison would be utterly inadequate to fill his progressive shoes? In this environment, standing on principle isn’t seen as a vital act of cultural and moral leadership; it makes you a sucker.

Not really, but that brings us to the binary choice. In 1998 the Democrats couldn’t bear to give the Republicans a win. The very thought was repugnant to them, even if a Republican win would still have left the nation with a President Gore. How many Democrats are saying today — when pondering Al Franken — that there is no way they will force out one of their own when the Alabama GOP is rallying around a man credibly accused of terrible sex crimes?

In this environment, standing on principle isn’t seen as a vital act of cultural and moral leadership; it makes you a sucker, a rube who allows your party to be beaten by a more Machiavellian opponent. Some of this is understandable. After all, in the private sector one rarely faces a situation where forcing out a sexual predator means “My enemies win.” Liberal filmmakers are crawling all over Hollywood. Getting rid of the likes of Harvey Weinstein is in a very real way an ideologically costless exercise — and even that small display of resolve took decades to happen.

Every week members of the media are getting caught in scandals, but MSNBC can take action against Mark Halperin or the New York Times can put Glenn Thrush on leave without potentially handing over their institutions to their ideological opponents. If ditching Halperin meant canceling Rachel Maddow’s show and handing her prime-time slot over to, say, Mark Levin, I wonder how many people would have suddenly been willing to accept his apologies and (in the words of a certain progressive activist organization) “Move on.”

The bottom line is that virtue — rightly understood — is hard. Defending a culture of integrity, respect, and honor means sometimes taking a short-term loss for the larger win. It means sometimes being willing to sacrifice for the greater good. It means that 51–49 is preferable to 52–48 if that one extra seat would have meant that a likely child abuser was in the Senate. Keith Ellison (or another progressive) is preferable to Al Franken if it means that our political culture is finally getting serious about respecting women.

Alabama voters and Democratic senators are in control of an important moral moment. Are they serious enough about character and integrity to make even the smallest political sacrifice to shore up a fraying national culture? It won’t be long before time marches on and the names of Roy Moore and Al Franken are lost to memory. Few people will remember who they were or why anyone worried about their political careers. What will survive, however, is a culture that has been either built, brick by brick, or demolished, brick by brick. The decision now is whether we build or tear down. We’d best choose wisely.

[bold, italics, and colored emphasis mine]

No comments:

Post a Comment