The road to Hades is paved with good intentions. And, I’d like to add, with consequentialist arguments.

A recent piece at Christianity Today’s blog “Thin Places” told readers that “Contraception Saves Lives.” Now most evangelicals, unlike faithful Catholics, are not opposed to contraception per se, but the article pushed the edge of the proverbial envelope.

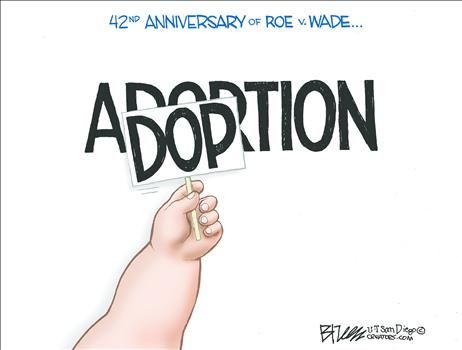

What has drawn the most attention was the article’s attempt to enlist Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger in the pro-life cause. While the piece acknowledged that Planned Parenthood is “the largest provider of abortions in the United States,” it maintained that this is not what Sanger would have wanted. Sanger, we are told, opposed abortion. And similarly, Sanger’s role in the eugenics movement was downplayed.

Well, the swift and loud critical response to the piece prompted a clarification by the editor of “Thin Places,” who acknowledged all of the criticism of their attempt to rehabilitate Sanger. For her part, the author subsequently wrote that she “did not accurately estimate how great a distraction the Sanger example would be.”

Well obviously she didn’t. But her mention of Sanger not only “distracted” people from the larger point she was trying to make—that providing contraceptives to poor women in the developing world would save lives—but also the moral reasoning that she employed in her argument.

The kind of moral reasoning is known as “consequentialism.” It holds that the rightness or wrongness of an act is only judged by its consequences or, perhaps, the motives behind the act. Now if that sounds like “the ends justifies the means” sort of talk to you, it is. This expression is the logical outcome of this kind of moral reasoning.

Consequentialism, like its subset utilitarianism, doesn’t concern itself with the intrinsic rightness or wrongness of an act. All that matters is whether the act leads to the desired outcome.

Now if you’re wondering “desired by whom?”, congratulations, you’ve identified one of the most dangerous things about consequentialism: There’s no logical limit to what can be desired or justified. And if you want to see where this can lead, look no further than the writings of Princeton’s Peter Singer. His views on abortion, euthanasia, and even infanticide may be repugnant, but they’re fully consistent with consequentialist principles.

Now, no one over at “Thin Places” can be remotely compared to Singer, but many of the arguments being employed are steeped in consequentialism. A pragmatic ethical reasoning runs through the original post, the clarification, and judging by the introduction to the series, it’s going to through the whole series.

What’s missing is any consideration of the intrinsic morality of contraception. Now, let me be clear: I’m not arguing here that contraception is wrong per se. I’m arguing that the way we argue about the issue is wrong.

Evangelicals are long past overdue in having a considered discussion about whether birth control is a right or a wrong thing, what kinds of birth control are morally ethical and acceptable, and which ones are not, and why.

And by “why” I mean in reference to first principles, such as considering the God-given meaning and purpose of sex within marriage first, before considering consequences.

The same failure of ethical reasoning is at work in discussions about same-sex marriage. Just this past week, reports came of another evangelical church—this time in San Francisco—that became a so-called “affirming congregation.” But evangelical proponents for same-sex marriage haven’t argued for it from first principles, or from the biological realities of “male and female as God created them.” Instead, their argument is that our previous approaches to the issue haven’t worked, or have been counterproductive, or have hurt peoples’ feelings.

Now while these are, of course, legitimate concerns, Christian moral reasoning involves more than this. For an act to be morally acceptable, both the means and the ends must be moral. The Christian can never say “let us do evil so that good may come.”

We might have the best of intentions in moving moral goal posts in order to achieve better ends. But it won’t make it right.

[bold, italics, and colored emphasis mine]

FURTHER READING AND INFORMATION -No matter how worthy or good a goal is, the use of immoral means is not justified in achieving that goal. The consideration of first principles, as John stated, requires that we reject consequentialism's "the ends justify the means" assumption.

Restoring All Things: God's Audacious Plan to Change the World Through Everyday People -

John Stonestreet, Warren Smith | Baker Books | May 2015 | Pre-order through Amazon

No comments:

Post a Comment