Maintaining the concept of “death” as a biological, rather than sociological, event is one of the few remaining impediments to exploiting the most weak and vulnerable among as mere natural resources.

If death can be “redefined”–an ongoing project in bioethics–to include the end of the subjective concept of being a “person,” then the unborn–supposedly, not yet persons–and those who through injury or illness have lost the ability to express personhood, can be deemed dead, or perhaps better stated, as good as dead.

This issue is discussed regularly above the public’s awareness in bioethics and medical journals. Every once in a while, I think it worth the time to bring some of this advocacy to a wider readership to alert my readers to what the elites in bioethics would like to impose upon us. From, “The Death of Human Beings,” by bioethicist N. Emmerich, in the medical journal, QVM:

"When we say that someone has died, we do not merely mean that some biological entity no longer functions. We mean that they, some unique mind or person, understood as a cognitive phenomena or psychological entity, has ceased to exist. Despite being a non-biological term, personhood admits of the application of the terms life and death and, furthermore, reflects the ordinary meaning of the terms."

We should think very seriously about the consequences of changing death from the irreversible biological end of the integrated organism, to the subjective determination that personhood and relevant “capacities” have ceased.

It would mean that clearly alive individuals could become exploitable–or used instrumentally–in the same way as we do biologically dead bodies now. That wouldn’t just mean live organ harvesting of persistently unconscious or minimally conscious patients–often proposed in organ transplant journals–but also experiments conducted on their living bodies.

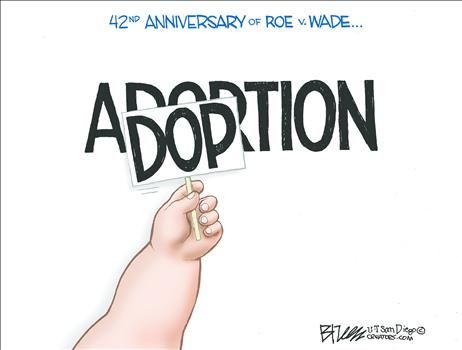

Such uses could also be applied on living fetuses, perhaps even, infants, who would be deemed not yet “alive” as human beings because they haven’t yet attained the self-awareness deemed necessary for personhood, and hence, “earned” their equal moral value.

You think I exaggerate? Ponder the profound and adverse consequences of this:

A severely anencephalic neonate is a human organism that may be alive (or dead) in the sense of zoe. However, they will never have a life in the sense of bios. On the account offered by Schofield et al. life begins at conception. We should, therefore, distinguish between the commencement of biological or organismic life and the point at which the fetus becomes a subject, and not just an object, of life.

This does not mean the matter is easily settled; as with brain death, brain life remains a contested notion.9 Nevertheless such conceptual difficulties should not lead us to simply reject such notions. Rather, we might accept that situating an essentially metaphysical and philosophical conception of personhood in the empirical and practical context of biomedicine presents inherent epistemological challenges.

Changing death from biological to sociological would open the door to profound evil.

Illustrating how mainstream this subversive approach to human life and death has become among the medical/bioethics intelligentsia, this article was listed as the “editor’s choice.”

I explore these and other dangers of “personhood theory” much more deeply in my just released book: Culture of Death: The Age of ‘Do Harm’ Medicine.

[bold, italics, and colored emphasis mine]

LifeNews.com Note: Wesley J. Smith, J.D., is a special consultant to the Center for Bioethics and Culture and a bioethics attorney who blogs at Human Exeptionalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment