Many rituals are associated with Inauguration Day in the United States: the Oath of Office, inaugural balls, and Washington-area residents whose party lost the election listing their homes on Airbnb, just to name a few. And then there’s a lesser-known ritual that’s just as established but even more important: the argument over the Mexico City Policy.

First instituted in 1984 by Ronald Reagan, the Mexico City Policy derives its name from the venue of that year’s U.N. conference on “Population and Development.” The policy states that, as a condition of receiving federal funds, non-governmental organizations agree they will “neither perform nor actively promote abortion as a method of family planning in other nations.”

Every time the White House changes party hands, the Mexico City Policy also changes. Like clockwork. So when Democrats like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama move in to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, they rescind the Mexico City Policy. When Republicans like George Bush and Donald Trump come to town, they restore the policy in some form.

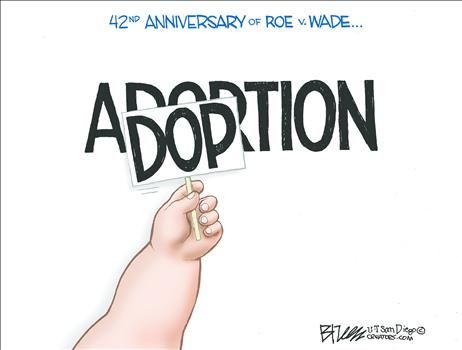

Each time the policy is restored, abortion advocates start wringing their hands, warning that the U. S. is putting women’s lives at risk. They cite figures about deaths from “preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth.” And recently, they’ve claimed that the latest iteration of the policy is forcing organizations to choose between treating HIV/AIDS and providing “life-saving reproductive health services.”

It’s not clear, of course, how in the world a policy specifically directed at abortion prevents anyone from addressing real health issues. And they conveniently omit the fact that the policy specifically exempts referrals in cases of “rape, incest, or endangerment of the life of the woman.”

As Elisha Dunn-Georgiou of Population Action International, recently acknowledged, “the policy does not reduce U.S. funding for health or family planning.” But it does take money from what she calls “the most competent providers of ‘sexual and reproductive health and rights’”—that is, pro-abortion advocacy groups like hers or Planned Parenthood.

So what’s really behind the dire warnings that accompany the reinstatement of the policy is funding. Groups that equate “women’s health” with “abortion rights” attack the Mexico City policy as a “health threat,” even if the only real threat is to their own bottom line.

But there’s also another reason for the hand-wringing over the Mexico City policy, one that even critics have been forced to admit: it’s a policy that works! The policy has forced non-governmental organizations to decide whether their priority is going to be abortion advocacy or women’s health. In the process, local people are questioning why so many foreigners and government officials consistently present abortion as a solution to all of their problems, when the U.S. government does not support it?

Well, here’s why. First, abortion really isn’t a solution for women’s health. The all-too-many deaths from pregnancy-and childbirth-related causes in developing nations have little to do with legalizing abortion, a point critics of the policy seem intent on obscuring.

Second, because Christian institutions provide one-third of the medical care in Africa, and they want to promote health, physical and spiritual, not a “culture of death.” That’s why they support the Mexico City Policy.

On the other hand, we shouldn’t be a bit surprised that groups like Planned Parenthood hate it. It denies their funding, and directly challenges their deep, historic, and ideological commitment to abortion on demand.

Which is why denying them funding overseas is a positive development. Now if we could only find a way to deny that funding here at home.

[bold, italics, and colored emphasis mine]

No comments:

Post a Comment