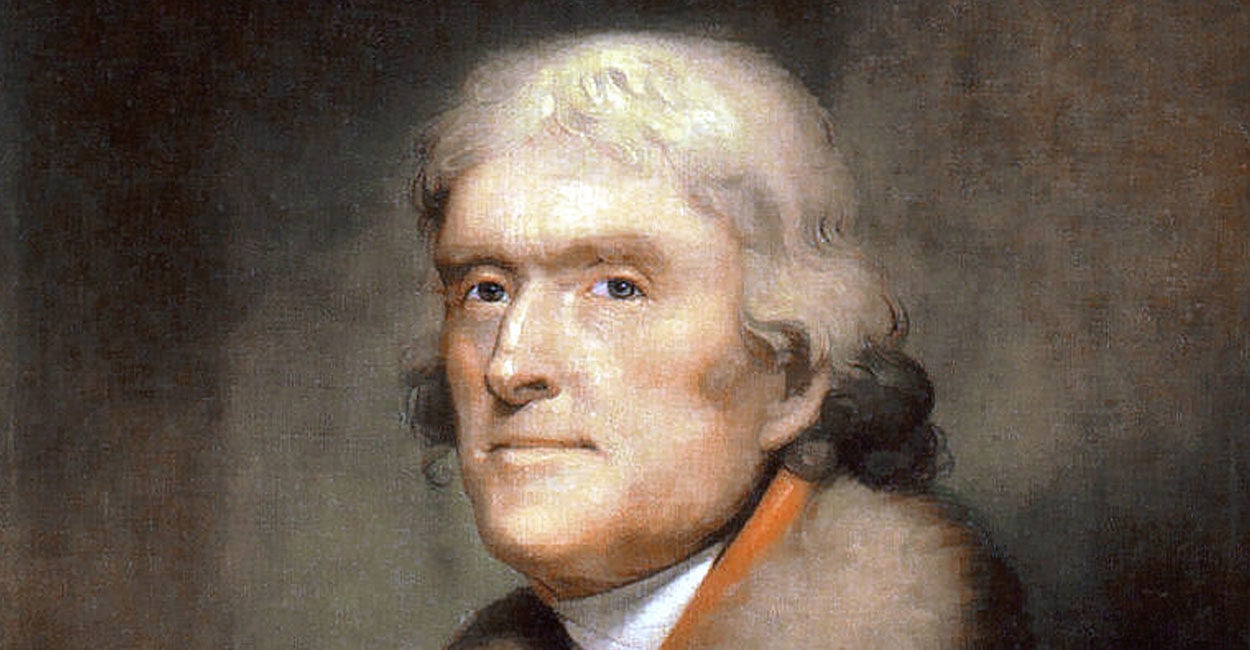

President Thomas Jefferson negotiated with France to broker the Louisiana Purchase, which nearly doubled the geographical size of the United States overnight. (Photo: World History Archive/Newscom)

Our current president prides himself on being the master of the deal. The upcoming summit with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un will certainly put his bargaining skills to the test.The stakes couldn’t be higher, since they involve the security of one of the most populous and economically vital regions in the world, and North Korea has shown little regard for agreements in the past.

If President Donald Trump successfully forges a deal that denuclearizes the Korean Peninsula, it will go down as one of the greatest deals in American history. With that said, it’s fair to ask whether history provides any lessons in the art of presidential negotiation. Of course, historical situations differ vastly, but it’s still fair to ask whether historical examples can provide any guidance for the general principles of high-stakes negotiation.

Perhaps there is no better place to look than what has been described as the greatest bargain in American history—the Louisiana Purchase. The deal was struck exactly 215 years ago this Monday. In the words of historian Henry Adams, the purchase was “next in historical importance to the Declaration of Independence and the adoption of the Constitution. It was unparalleled in diplomacy because it cost almost nothing.”

The purchase did cost something, but as American schoolchildren learn, that cost was absurdly low: $15 million for 828,000 square miles of land, or 3 cents per acre. Even if adjusted for inflation, the price is still a low 60 cents per acre.

More recent research includes the amount the United States paid to Native Americans in lopsided treaties ($2.6 billion, or $8.5 billion adjusted for inflation)—still far below the worth of the land.

The Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States, and that doubling was a precursor to its eventual domination of the North American continent and its rise to world power. It reduced the hold that European powers had on the continent, thereby mitigating the threat they posed to the young republic. It was the greatest deal in American history, but how did Jefferson pull it off?

Part of the answer lies in Thomas Jefferson’s own complexities.

Our third president, whose 275th birthday was on April 13, is known for the eloquence of his pen and his renaissance-man lifestyle, but this image belied his cutthroat political instincts. Jefferson was a shrewd politician, through and through. As secretary of state under George Washington, he had secretly funded an opposition party right under the first president’s nose.

Just weeks into Jefferson’s presidency, he learned that France was reacquiring the Louisiana Territory from Spain. The prospect of an aggressive Napoleon ruling territory right next to the United States alarmed the new president, so he made a number of moves that any shrewd head of state would.

First, Jefferson drew a red line with France. Jefferson was a renowned Francophile—he loved France, and some even accused him of having “a womanish attachment” to the country. At the same time, he was a staunch critic of Great Britain. But he knew the threat that Napoleonic France would pose to the young nation. Writing to his envoy in France, Jefferson made clear how France’s acquisition of North American territory was being seen in the United States: “The cession of Louisiana and the Floridas by Spain to France works most sorely on the U.S. … [and] reverses all the political relations of the U.S.”

The reason this harmed U.S. political relations was because whoever controlled Louisiana would control New Orleans. Jefferson continued:"There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market, and from its fertility it will ere long yield more than half of our whole produce and contain more than half our inhabitants. France placing herself in that door assumes to us the attitude of defiance… . The day that France takes possession of [New] Orleans … we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation." Despite Jefferson’s hatred of Britain, he now found himself threatening to join forces with his former enemy to defeat his beloved France.

Second, Jefferson played the age-old diplomatic game of back-channel diplomacy. Despite establishing a red line, he knew that his infant country could ill-afford a war with a European superpower. So he engaged in multiple lines of communication with France. This included making use of his minister to France, Robert Livingston, but it also involved sending a more personal envoy, James Monroe, to join Livingston in his negotiations with the French.

But Jefferson didn’t stop there. He also communicated through Pierre Samuel du Pont, a wealthy Frenchman in America with connections to the French regime. Indeed, it was du Pont who is often credited with suggesting a purchase of territory as a solution.

Further, Jefferson made use of a French diplomat in the United States, Louis-Andre Pichon. Through Pichon, the Jefferson administration fed information to the French, raising the specter of American cooperation with the British against the French.

Third, Jefferson had the wisdom to listen to advice contrary to his own inclinations—and that advice often came from his brilliant secretary of state, James Madison. Madison’s genius and political skills rivaled and arguably exceeded that of Jefferson’s.

After an agreement was signed, Jefferson, a strict constructionist, worried that he was stretching the powers of the federal government by acquiring territory—an issue not addressed in the Constitution—and considered calling for a constitutional amendment. Madison, however, believed that time was of the essence, especially since he had heard rumors that Napoleon was reconsidering the deal. He successfully convinced Jefferson to accept the agreement.

This brings up the fourth lesson: Know how far you are willing to go, even if it means going past your ideological limits.

As I said earlier, Jefferson was known as a pro-French, anti-British strict constructionist. And yet, during this episode, he threatened to side with the British against the French and then disposed with his strict constructionist tendencies, forgoing an amendment for the sake of his country’s interest. As Jefferson later wrote: " A strict observance of the written laws is doubtless one of the high duties of a good citizen, but it is not the highest. The laws of necessity, of self-preservation, of saving our country when in danger, are of higher obligation. To lose our country by a scrupulous adherence to written law, would be to lose the law itself, with life, liberty, property, and all those who are enjoying them with us; thus absurdly sacrificing the end to the means."

With all that said, the reality of the Louisiana Purchase is that many developments cut in America’s favor that were outside of its control. These include the following:

The largest slave uprising in modern history was occurring in Haiti, a French colony, which weakened France’s position in the Western Hemisphere—it had become a quagmire resulting in 50,000 deaths.

The resumption of war between the British and the French in 1803, which focused Napoleon’s ambitions back on the European theater and increased his need for quick cash. The mercurial nature of Napoleon Bonaparte. He was not afraid to make an impulsive and consequential decision, namely getting rid of France’s possessions in North America.

The Haitian Revolution and the resumption of war with the British undoubtedly played a major role in convincing Napoleon to give up Louisiana. And perhaps that is the biggest lesson when it comes to deal-making: Results often come from events outside of one’s control.

How did Jefferson secure the greatest deal in American history? He did the things that most statesmen would do: draw a red line and use multiple channels of diplomacy. He also did what some statesmen do: listen to those who disagree with you and be willing to stretch your ideological limits. But he also was the beneficiary of much good fortune. Perhaps the greatest lesson here is humility in the face of events that one cannot control.

[italics and colored emphasis mine]

Richard Lim is the host of "This American President," a history podcast.

Check out Richard Lim’s podcast, “This American President.”; http://www.thisamericanpresident.com/

"How George Washington’s Sterling Character Set an Example for the Ages" - Richard Lim / @ThisAmerPres / December 23, 2017; https://www.dailysignal.com/2017/12/23/george-washington-and-the-elegant-simplicity-of-character

I like the points made in this article, such as listening to advice by others you disagree with, setting clear expectations, and being humble in the face of events outside of one's control. The point I'm not sure about is point 4, which says that sometimes one must bend the rules to reach a good end. They don't say, "The ends don't justify the means," without good reason. Strict versus loose constructionism is probably the root of all disagreement between liberals and conservatives. (Btw, strict constructionism believes the government can only do what is explicitly allowed by the Constitutionism, but loose constructionism believes the government is only prohibited from doing what is specifically prohibited in the Constitution.) That's why, as the article says, we need to know how far we're willing to go, but how far is too far is still an open question.

ReplyDelete-herb