Many articles this time of year wrangle over the specific details surrounding Christ’s birth—Did it really take place in a stable? Was it really in winter? When did the Magi show up? But the core of the story is unmistakable, because it’s taken straight from the pages of the Gospels. And we see it depicted in every nativity scene.

Nativity scenes are so commonplace in December, we can easily forget how much they confront our self-absorbed age. Kneeling beside the manger is a girl of no status or means who said “yes” to a Divine summons to be a part of the central event in all of history. When confronted with the profound and unexpected gift of being mother to Christ—a burden she would bear not just for nine months but for a lifetime—she accepted. Because of her obedience, our burdens are lifted.

Beside her stands a quiet man, remembered by the world as just and noble because he thought of the good of his betrothed over his own reputation. He gave of himself without reservation to raise the Son of God.

And of course, there’s the babe: Jesus Himself. His self-giving was by far the most profound. Not only did He empty Himself of the glory He had with His Father from eternity, He adopted the form of a servant, bore our infirmities, and ultimately shouldered our guilt on the cross.

I am better able to see the self-giving underpinnings in the nativity story because of a powerful article in the Yale Daily News from over a decade ago. Bryce Taylor, who was (I believe) just nineteen at the time, wrote about the Christmas story and the familiar picture of the manger scene as a critique of our me-first culture.

“Throughout the Christmas narrative,” he observes, “we find as a recurring motif the idea that adversity must be met with self-sacrifice…Mary must bear the shame and unbridled gossip that accompany premarital pregnancy; Joseph must decide either to part with Mary or raise a child who is not his own. Even the wise men, to quote a poem by T. S. Eliot…[must travel through] ‘the cities dirty and the towns unfriendly.’”

Especially at this time of year, we look on all this self-giving—most of all on God’s gift of Himself—with awe and admiration. Even non-Christians see the beauty in this kind of self-sacrifice. Throughout the year, we revere soldiers and firefighters and first-responders, among others, for their self-sacrifice. Yet as Taylor pointed out in his article, the December stampede to consume TVs, gaming systems, and cars clashes with the theme of self-emptying found in the nativity.

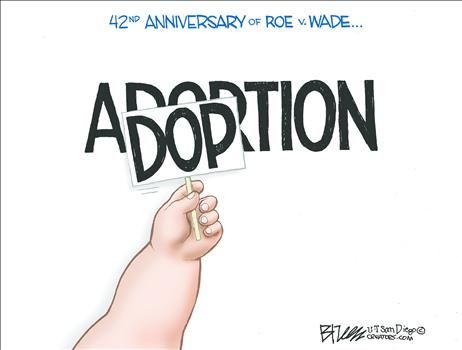

Less than a month after the holiday bustle, we annually mark the anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the ultimate assertion of my rights over the lives of others. The contrast between Mary’s “yes” to an unexpected Guest and the “no” of our culture and our judiciary could hardly be sharper, or more deadly.

Yet rather than rehearse the familiar and necessary arguments to be made against abortion, Taylor made a surprising move and appealed to his predominantly secular readers’ sense of beauty. “Which is more beautiful,” he asks, “more noble, more admirable: the vociferous American woman demanding the right to preserve her body from the intrusion of a baby, or the young Jewish girl in the Christmas story who sacrifices her plans and her reputation in a gesture of openness to the gift of new life? What is more worthwhile: the life that seeks convenience, or the life that accepts the call to sacrifice? Sincere contemplation of the nativity scene yields an unambiguous answer.”

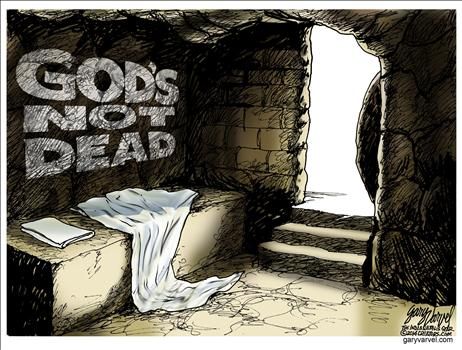

Dostoevsky wrote that “beauty will save the world.” In the self-giving incarnation of God the Son, and all the acts of self-giving that surrounded that first Christmas, we get a glimpse of what he meant. Each December, the secular world is confronted with nativity scene reminders that life is better than death, that birth is more lovely than abortion, and that sacrifice on behalf of another is more beautiful than ending a life in the name of freedom. And (beauty of beauties!) these scenes proclaim the arrival of the only One who can ever set us free from our own selfishness. The reminders are simply everywhere.

[italics and colored emphasis mine]

"Taylor: Christmas now and once before" - Brycs Taylor, EC 05, 2008; https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2008/12/05/taylor-christmas-now-and-once-before/#disqus_thread

One would be hard-pressed to invent a scene more beautiful than that of the Christmas nativity. The newborn child, his young mother and her betrothed, the shepherds, the wise men, the ox and the donkey, all with the Star of Bethlehem beaming gaily — this, no doubt, is the stuff of poetry. But poetry aside, the nativity scene represents a story of hardships and terrible difficulties. Mary must bear the shame and unbridled gossip that accompany premarital pregnancy; Joseph must decide either to part with Mary or to raise a child who is not his own. Even the wise men, to quote a poem by T. S. Eliot, have “a hard time” of it, traveling through “the cities dirty and the towns unfriendly.”

But of course the utmost hardship in the story is that of the little baby lying in the manger. In the form of this baby, God himself — according to Christian teaching — has stepped down from heaven, put on flesh, adopted the lowly nature and the vulnerabilities of the humans he created. The infinite and almighty has assumed finitude and dependence. Throughout the Christmas narrative, we find as a recurring motif the idea that adversity must be met with self-sacrifice: Mary’s sacrifice for her child, Joseph’s sacrifice for Mary and her child, and above all Christ’s sacrifice for humanity.

More than nine out of 10 Americans celebrate Christmas, including many who do not profess the Christian religion. The Christmas narrative has exerted an immeasurable force on our societal conscience and consciousness. And yet we have achieved the remarkable feat of coupling that narrative with another, quite different narrative: that of the commercial.

The commercial tells us that a successful and fulfilling Christmas is one in which we receive the newest iPod, the latest gaming system, the highest-definition television screen and (to make it a December to remember) a brand-new Lexus. The meaning of Christmas is twofold: Celebrate the birth of Christ, and get a lot of sweet new stuff — and not necessarily in that order. On the same day we pay homage to self-sacrifice and self-indulgence, difficulty and ease, suffering and convenience. We will bow to the manger, but only on the condition that some gold, frankincense and myrrh be tossed in there with the child.

This is an exaggeration, of course. Most Americans would survive a Christmas in which they failed to receive the most expensive new gadget, and many, it is true, deem themselves more blessed in giving than in receiving. Nevertheless, the distinctly American ability to pair the spirit of the nativity scene with the spirit of the commercial points to a tension lying deep within our national heritage and identity.

Our dominant political philosophy has told us that we have an inalienable right to pursue happiness; our dominant religion has told us to carry a cross. Our prevailing economic system is premised on self-interest; our most prevalent religion is premised on the commandment to serve the interests of others. The characteristically American attitude towards money says more is better; the characteristically Christian attitude towards money says, in the words of G. K. Chesterton, that “to be rich is to be in peculiar danger of moral wreck.”

But somehow we manage, during the Christmas season, to hold together these two contraries — what we might call the “will to ease” and “receptivity to hardship.” Less than a month after Christmas Day, however — on Jan. 22, to be precise — the tension erupts into bitter discord. On this day, the anniversary of Roe v. Wade, hundreds of thousands of protestors meet in Washington to march on the Supreme Court in protest of what is perhaps the gravest manifestation of our nation’s will to ease. Others celebrate the occasion in commemoration of what they perceive to be a liberation from unfair hardship.

Arguments over abortion continue to rage, as they must. But perhaps we would do well, on occasion, to set aside dialectical jousts and consider both sides with respect to their aesthetic appeal.

Which is more beautiful, more noble, more admirable: the vociferous American woman demanding the right to preserve her body from the intrusion of a baby, or the young Jewish girl in the Christmas story who sacrifices her plans and her reputation in a gesture of openness to the gift of new life? What is more worthwhile: the life that seeks convenience, or the life that accepts the call to sacrifice? Sincere contemplation of the nativity scene yields an unambiguous answer.

Bryce Taylor is a sophomore in Silliman College.

the disorder of the world. - Karl Barth

December 15 | SOUTH ASIA - An Open Doors partner shares about working with traumatized believers: “… It is a brutal moment when you witness your beloved sister or brother have a flash back to a deep pain. Pray for our team for wisdom, discernment, mercy and humility.”

Representative name or photo used to protect identity

No comments:

Post a Comment