Forty-two years ago, in Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton, the Supreme Court tried to settle the abortion debate by declaring the Constitution somehow creates a right to abortion in all fifty states. There is nothing in the Constitution that requires abortion in all 50 states, and that’s why Roe is rightly viewed as an activist decision, as explained in this Heritage paper:

"Judicial activism occurs when judges decline to apply the Constitution or laws according to their original public meaning or ignore binding precedent and instead decide cases based on personal preference. Labeling as ‘activist‘ a decision that fails to meet this standard does not express policy disagreement with the outcome; it expresses disagreement with the judge’s conception of his or her role in our constitutional system." [http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2013/06/how-to-spot-judicial-activism-three-recent-examples]

The result of this judicial activism has been three distinct types of harm: on the substance, on the process and on the rights of conscience.

On substance, by preventing states from making common-sense compromise policy on abortion, untold numbers of babies and women have been harmed. Look no further than Kermit Gosnell’s house of horrors. Or consider the fact that the U.S. is one of only seven countries in the world—alongside North Korea and China—that allows elective, late-term abortions after 20 weeks.

On process, by removing the issue of abortion regulation from the democratic process, the Court has created a 40+ year culture war. No issue in American public life is more contentious than abortion politics every election cycle. The Court short-circuited constitutional self-government on this issue.

On the rights of conscience, by unilaterally creating a “right” to abortion, the Court created a situation where for the past 40 years abortion funding has been a constant source of religious liberty concerns—most recently with the coercive Department of Health and Human Services mandate.

Why would the Court want to repeat these mistakes now on marriage?

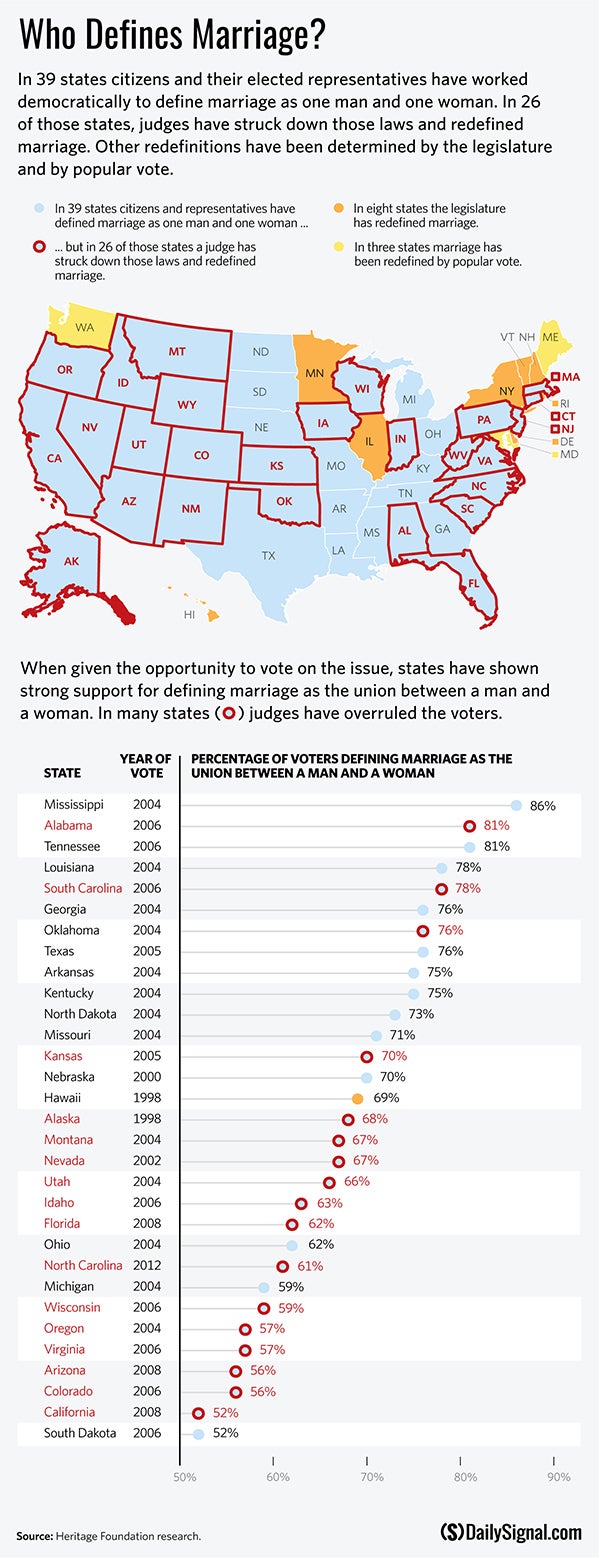

After all, there simply is nothing in the Constitution that requires all 50 states to redefine marriage. Whatever people may think about marriage as a policy matter, everyone should be able to recognize the Constitution does not settle this question.

Unelected judges should not insert their own policy preferences about marriage and then say the Constitution requires them everywhere. Since nothing in the Constitution requires the redefinition of marriage, as explained in this Heritage legal memorandum [http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2015/03/memo-to-supreme-court-state-marriage-laws-are-constitutional], a Supreme Court ruling redefining marriage everywhere would simply be an act of judicial activism.

Perhaps the Court doesn’t want to repeat the mistakes of Roe v. Wade. Indeed, the justices on Tuesday gave voice to each and every one of these three potential harms that could occur due to judicially imposed redefinition of marriage.

On substance, judicially redefining marriage could cause harm to marriage itself—and thus to spouses and children.

No one knows with certainty how redefining marriage will harm the institution of marriage. The lawyer defending the state marriage laws certainly made good arguments that it’s reasonable to think it could cause harm.

So what’s the rush to have the Court strike down state laws that define marriage as a union of husband and wife? Why should, as Justice Stephen Breyer asked, “nine people outside the ballot box … require states that don’t want to do it to change … what marriage is?” Breyer then asked, “Why cannot those states at least wait and see whether in fact doing so in the other states is or is not harmful to marriage?” Wait and see. Justice Anthony Kennedy said the same thing:

Well, part of wait and see, I suppose, is to ascertain whether the social science, the new studies are accurate. But that it seems to me, then, that we should not consult at all the social science on this, because it’s too new. You think you say we don’t need to wait for changes.

Clearly, we do need to wait and see what the consequences of redefining marriage will be. And that’s why the Court shouldn’t attempt to settle this once and for all. Judicial activism on the marriage issue could cause harm to the substance of marriage by not allowing citizens and their elected representatives the ability to arrive at the best public policy for everyone.

On process, judicially redefining marriage could cause harm to civil peace and self-government.

Chief Justice John Roberts noted that a court-imposed 50-state solution would not lead to civil peace, but to anger and resentment. If the Court redefined marriage, “there will be no more debate.” And this would cause problems: “closing of debate can close minds, and it will have a consequence on how this new institution is accepted. People feel very differently about something if they have a chance to vote on it than if it’s imposed on them by the courts.”

Indeed, just as Roe v. Wade created a culture war on the abortion issue, an activist Court ruling redefining marriage everywhere could create a similar backlash.

On the rights of conscience, judicially redefining marriage could cause harm to religious liberty and the rights of conscience.

After all, the Obama administration’s Solicitor General himself, Donald Verrilli, admitted that religious schools that affirm marriage as the union of a man and a woman may lose their non-profit tax-exempt status if marriage is redefined, saying: “It’s certainly going to be an issue. I don’t deny that. I don’t deny that, Justice Alito. It is it is going to be an issue.”

But where marriage has been redefined democratically, religious liberty can best be protected. Justice Antonin Scalia explained that in the states “They are laws.” He continued:"They are not constitutional requirements. That was the whole point of my question. If you let the states do it, you can make an exception. … You can’t do that once it is a constitutional proscription." Scalia repeated himself, almost verbatim, mere minutes later: “That’s my whole … point. If it’s a state law, you can make those exceptions. But if it’s a constitutional requirement, I don’t see how you can.” And that’s why judicially redefining marriage could cause harm to religious liberty and the rights of conscience.

In sum, when you consider the harms that judicial activism caused on the abortion issue, and when you see the justices given voice to the potential harms of judicially imposed marriage redefinition, it seems a much better path forward to respect the constitutional authority of citizens and their elected representatives to make marriage policy in the states.

[bold, italics, and colored emphasis mine]

Ryan T. Anderson, Ph.D., researches and writes about marriage and religious liberty as the William E. Simon senior research fellow in American Principles and Public Policy at The Heritage Foundation. He also focuses on justice and moral principles in economic thought, health care and education, and has expertise in bioethics and natural law theory. Read his research.

No comments:

Post a Comment