When Stephen Jacobs decided to pursue his doctorate, he knew a question about the beginning of life might be controversial – but he didn’t know how controversial until he took the idea to his advisors. The result, the College Fix’s Daniel Payne explains, was a grueling five-year journey that may culminate with Jacobs never working in the field again.

Back in 2014, when Jacobs first started mulling the research over in his mind, he settled on a national survey of biologists. The goal was to ask thousands of scientists at American institutions: “When does a human’s life begin?’” After talking with his advisors, mentors, and other students in the program, he said he kept hearing the same thing, “that I should not research the abortion debate… because of who I was: a white, Christian man.”

Several people would have been deterred. Stephen wasn’t. After plenty of fits and starts, the survey got underway. Almost immediately, Payne writes, the trouble began. When the answers started pouring in, Jacobs was disappointed to see that he was being “ridiculed, mocked and defamed; accused of committing academic dishonesty, politicizing science and conducting his work with personal bias; compared to the Ku Klux Klan; and in general painted as an unprofessional radical who was, in one academic’s words, ‘not deserving of a PhD degree.’”

Even his advisor told Jacobs he would “step down.” Eventually, he did. “If I continued the research and, if he stayed on my committee, he would be unlikely to approve my dissertation. To say I was devastated would be an understatement. I was on my way to borrowing a quarter-of-a-million dollars to finance my education; I had turned my back on opportunities to make a ton of money as a corporate attorney; I had refused to sit for the bar so I would not be tempted by a legal career when things got tough; I had endured insults about my religion, accusations about my motivations, and attacks on my personal and professional integrity — all so I could do this work.” He was even reported to the school’s ethics committee, where the University of Chicago agreed to let him continue with his data gathering. [italics and colored emphasis mine]

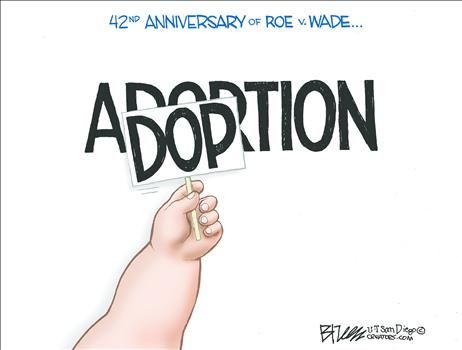

Despite all of the difficulties, the results proved to be worth it. He discovered that “whatever their politics, large majorities of biology professors support the pro-life contention that human lives begin at the moment of fertilization.” Three quarters of the scientists he questioned replied that conception – not heartbeats or viability or birth – is when a human life starts. Even more amazingly, the pro-abortion biologists agreed. “While nearly 90 percent of ‘very pro-life’ respondents answered that it begins at fertilization, still nearly three-quarters of ‘pro-choice’ respondents answered the same. Around three-fifths of ‘very pro-choice’ respondents felt the same.”

So much for Planned Parenthood’s “That’s a blob of tissue,” Christine Quinn’s “When a woman is pregnant, that’s not a human inside of her,” or Senator Barbara Boxer’s “It’s a life when you bring your baby home.” Jacobs’s research makes it clear where science stands. And it’s his goal to use those answers to move the abortion debate away from “When does life begin?” to “Is it okay to kill unborn humans.” “Let’s stop debating whether a fetus is a human and start debating whether all humans have rights and, if so, how to balance one human’s right to abort and another human’s right to life,” he told Payne.

Although Jacobs knows he might never find work in his field – “I’ve been regularly told I can’t get a job in academia. I’ve been told don’t try – he thinks the personal agony has been worth it. “I knew what was going to happen before it happened. I told myself I was going to do this for the sake of research, not for the sake of my career.” But research isn’t the only thing that benefited – so have untold numbers of unborn children, who one day might have Jacobs’s science to thank for building a case to save them.

[italics and colored emphasis mine]

No comments:

Post a Comment